Highlights

Are violence interrupters effective? Does CURE violence work?

A respected national criminal justice publication states that in CURE Violence initiatives, “Shootings Fell By 73 Percent.” Is this misleading?

Author

Note

Much of this article focuses on new initiatives as reported by media–CURE Violence-Atlanta and CURE violence Milwaukee.

Opinion

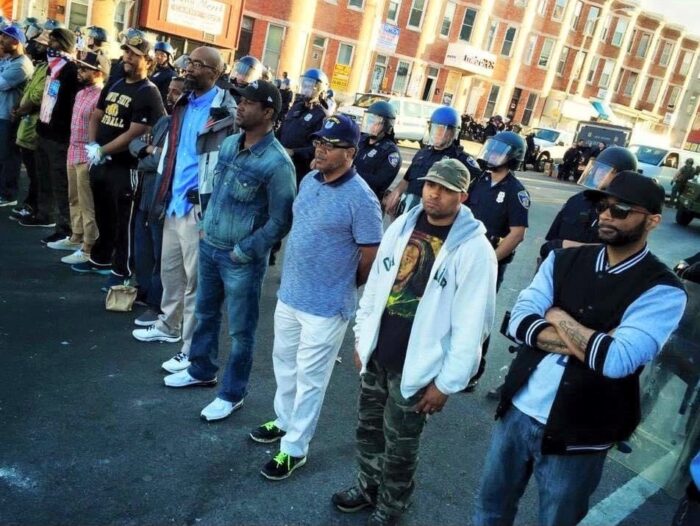

I worked as a federally funded street counselor in Baltimore City during college after I left law enforcement. I was a violence interrupter.

The people I served were approachable and I enjoyed their company, but it was obvious that I was in way over my head. The complexity of their problems was overwhelming. I’m pretty sure they taught me far more than I taught them.

One who was thrown out of school for fighting wanted to go back. His intelligence was obvious. I convinced the school system to give him another try. His father wouldn’t sign the papers on the basis that he didn’t need a high school education so why should his son?

I stood in between two who were fighting. I was hit (not hard) by both. They insisted that their right to fight each other should not be interfered with.

The examples of my frustrations-inabilities are many.

Alternatives

Cities throughout the country are contemplating alternatives to law enforcement. Gallup states that the majority of Americans believe that law enforcement must change in light of alleged racial injustices and endless negative publicity.

People have a simplistic view of crime and criminals. It made sense for many to create correctional boot camps for young offenders on the premise that, “it gave me structure and discipline. It worked for me. It will work for them.”

Boot camps didn’t work per research.

We believed that rehabilitation or educational programs would reduce criminality for inmates and people on parole and probation. Per a Department of Justice literature review, they don’t.

We’ve tried everything from social work programs to street lighting to crime prevention through environmental design to throwing millions of dollars to improve specific high crime communities.

Most didn’t work.

Using social workers to respond to non-emergency calls hasn’t been fully evaluated but at least one program claims to take a week or more to respond to calls and describes the situation as a “crisis” of non-response.

To date, the only thing that seems to work per a US Department of Justice literature review is proactive policing, the same modality heavily criticized by many in high crime areas.

Some claim that police proactivity was a partial reason for many of the riots and disturbances that shook the country and caused over two billion dollars in damages per a report from insurance companies.

Sources: All evaluations mentioned are available at Crime in America.

Is Cure Violence The Answer?

We have a well-funded effort using violence interrupters to step in between waring people to prevent more violence; Cure Violence funded by the Annie E. Casey Foundation.

Every city using this model will configure the program differently but the heart and soul of street-level efforts are credible spokespeople, often former offenders, who will listen to concerns and offer solutions to rampant violence. Some are emergency room-based.

Like boot camps and educational programs for correctional populations, it all makes intuitive sense. We’ve all had credible people in our lives that have talked us down from doing something stupid. Like so many other social efforts, we feel in our very being that this will work.

Shootings Fell By 73 Percent

From The Crime Report: The Annie E. Casey Foundation reports that in communities within Atlanta and Milwaukee where Cure Violence, an international gun violence-prevention model was implemented, shootings fell by as much as 73 percent, the Juvenile Justice Information Exchange (JJIE) reports.

The model has already been successfully implemented in cities around the county, like in Chicago (where shootings have declined by 47 percent), Philadelphia ( 30 percent), and New York (63 percent) — as well as internationally in Trinidad and Tobago (reducing violence by 45 percent), according to the Cure Violence Global (CVG) website impact page.

Why Is This Important?

Criminologically speaking, most violence is concentrated in small sections of cities. It’s a matter of focusing resources on places and people (especially repeat offenders) in very high crime areas. If the literature is correct, a focus on the right areas and people “should” reduce violence in and beyond the target areas.

Does CURE Violence work? Let’s take a look at the literature.

Evaluations-Saint Louis Today Focusing on Milwaukee (quotes edited for brevity)

In Baltimore, a 2012 study showed statistically significant improvements in gun violence in three of four neighborhoods.

But a more comprehensive follow-up released in January 2018 demonstrated less of an impact. Three of seven sites — more had opened over the years — were shut down after disappointing results.

Daniel Webster, a professor of American health from Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, said it’s a good thing that St. Louis is investing in Cure Violence, but cautioned that the method has limitations. Other, longer-term services should be offered to ensure success, he said.

“Look at things like what New York City is doing, where they took Cure Violence and really kind of built it out,” said Webster, who co-authored the Baltimore studies.

Webster also said that Cure Violence tended to do better in geographically isolated neighborhoods, such as Baltimore’s Cherry Hill. “Most of the violence that occurs in Cherry Hill is, in essence, internal in nature,” Webster said. Other neighborhoods attract outsiders — but Cure Violence staff “don’t have relationships with these other individuals coming in from other areas.”

And he believes working with police — interrupters in Milwaukee don’t — can benefit the program’s effectiveness, even if it’s just a one-way flow of information from police to Cure Violence staff, Saint Louis Today.

Evaluations-Milwaukee Journal Sentinel (quotes edited for brevity)

Academic researchers have evaluated Cure Violence in Chicago, Baltimore (the Safe Streets program), Brooklyn (Save Our Streets), Phoenix (the Truce program) and Pittsburgh (One Vision One Life).

The findings of the most prominent studies are generally mixed, according to research published in 2015 in the Annual Review of Public Health.

Although each evaluation showed at least some effectiveness locally, the authors wrote, none could “clearly disentangle the results from national and regional trends in violent crime.” Studies also varied based on sample design, selection of comparison neighborhoods and implementation strategies, Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

Chicago (quotes edited for brevity)

In 2013, the city of Chicago did not renew a million-dollar grant to Cease Fire — the name of Illinois’ Cure Violence program. Some city officials didn’t feel the program worked closely enough with the state, according to a 2017 story by NPR. Others disliked many of the violence interrupters were former criminals, the story said.

The program lost most of its funding from the state in 2015 during a long budget battle. It now runs a scaled down version with private donations and grants.

But in New York City, the program has been fully embraced, according to NPR. In 2017, New York City was investing $25 million in its Cure Violence efforts, WPR.Org.

The Annual Review of Public Health (quotes edited for brevity)

As documented in the Annual Review of Public Health: All previous studies of CV (editor’s note-CURE Violence) have faced common challenges: The principal outcomes of interest were changes in aggregate rates of violence and/or shootings measured at the neighborhood level, and they took place during a time when violent crimes (most serious crimes, in fact) have been declining nationwide (editor’s note-violent crime was falling nationally and considerably at the time of cited CURE programs and evaluations).

The findings of the most prominent studies of CV to date are generally mixed. Each evaluation revealed at least some evidence in support of the approach at the level of jurisdictions or communities, but none of the studies could clearly disentangle the results from national and regional trends in violent crime; in addition, there were always confounding effects from factors related to sample design, selection of comparison neighborhoods, and variations in implementation, 2015 in the Annual Review of Public Health.

So Does It Work?

Per the evaluations and reporting above, we don’t know.

The backgrounds of most involved in the justice system include child abuse and neglect, PSTD, brain damage, school problems, mental health issues, and substance abuse. Many are repeat offenders. Many have histories of violence (as documented in the Annual Review of Public Health).

Given the complexity of offending, does it make sense that violence interrupters can break through a person’s entire history to effect change?

Per the parole and probation agents I worked with, most offenders have chips on their shoulders the size of Montana.

Possibly, according to the data, it “may” work. But proclaiming that “Shootings Fell By 73 Percent” in a respected national criminal justice publication is, based on the data, simply disingenuous. It gives the impression that huge decreases in violence are happening in entire cities or large areas of cities. That isn’t the case.

Most of the examples provided show small numbers of reductions in shootings or violence. Smaller numbers can show big percentage decreases. Most are in small sections of cities. Most of the cities have intense violence problems.

Milwaukee was recently cited as having one of the highest percentage increases in homicides in 2020. The PBS News Hour report recently described Atlanta as a warzone due to increased violent crime.

Where is CURE Violence in all of this? Is my question fair? If you buy the criminological theories that focusing resources on high crime places and people will reduce violence, it is.

Working With Repeat Offenders

The recidivism rates of people leaving prison or on parole or probation are extremely high with the overwhelming number being rearrested, often multiple times. Most former inmates are returned to prison. Ninety percent (or more) of arrests are based on new crimes, not technical violations.

As stated, most correctional programs offered to offenders didn’t work and when they did, the percentage increase in successful offenders was small. If the vast majority of medical interventions or vaccines didn’t work, there would be a national outcry to shut them down. When it comes to programs for offenders, failure has produced zero interest.

If the best and brightest in criminology and evaluations and dedicated, knowledgeable parole and probation agents can’t figure out a way to reduce crime within a captured population (includes those on parole and probation), then does it seem plausible that former offenders and others with street credibility could?

Conclusions

We shouldn’t be afraid of trying new things. The example I gave of social workers responding to non-emergency calls being “in crisis” is just one program.

It’s the same with violence interrupters. It may work. Who knows? The data is simply mixed and the numbers “saved” are relatively small.

All I do know is that there are endless “intuitive” efforts that have failed.

The Annie E. Casey Foundation is an advocacy organization and advocates can stretch the truth.

The effectiveness of violence interrupters remains an open question, which is why when you look at media coverage for “CURE Violence-Atlanta” and “CURE Violence Milwaukee” (the current initiatives) they have little mainstream coverage. I assume reporters have the same skepticism as me after reading the data.

And if CURE Violence really did reduce shootings by 73 percent and the numbers and areas served were substantial, then they would win the Nobel prize and the world would be running to them for an effective solution to violence. To my knowledge, that hasn’t happened.

Advocates are pleading for a public health approach to criminality and violence interrupters seem to make sense.

But I interviewed hundreds of successful offenders who are now crime and drug-free who are doing well for radio and television shows. When asked why so many of their counterparts didn’t do well, they tell me that they have demons they (and anyone else) can’t control.

It’s my guess that the same applies to violence interrupters and their efforts to reduce crime by intervening in the lives of people at risk. It just all seems too good to be true. I would be happy to be proven wrong.

See More

See more articles on crime and justice at Crime in America.

Most Dangerous Cities/States/Countries at Most Dangerous Cities.

US Crime Rates at Nationwide Crime Rates.

National Offender Recidivism Rates at Offender Recidivism.

An Overview Of Data On Mental Health at Mental Health And Crime.

The Crime in America.Net RSS feed (https://crimeinamerica.net/?feed=rss2) provides subscribers with a means to stay informed about the latest news, publications, and other announcements from the site.